Universal Basic Income

“Universal basic income (UBI), also called unconditional basic income, basic income, citizen’s income, citizen’s basic income, basic income guarantee, basic living stipend, guaranteed annual income, universal income security program or universal demogrant, is a theoretical governmental public program for a periodic payment delivered to all citizens of a given population without a means test or work requirement. A basic income can be implemented nationally, regionally, or locally. If the level is sufficient to meet a person’s basic needs (i.e., at or above the poverty line) it is sometimes called a full basic income; if it is less than that amount, it may be called a partial basic income.”

……………

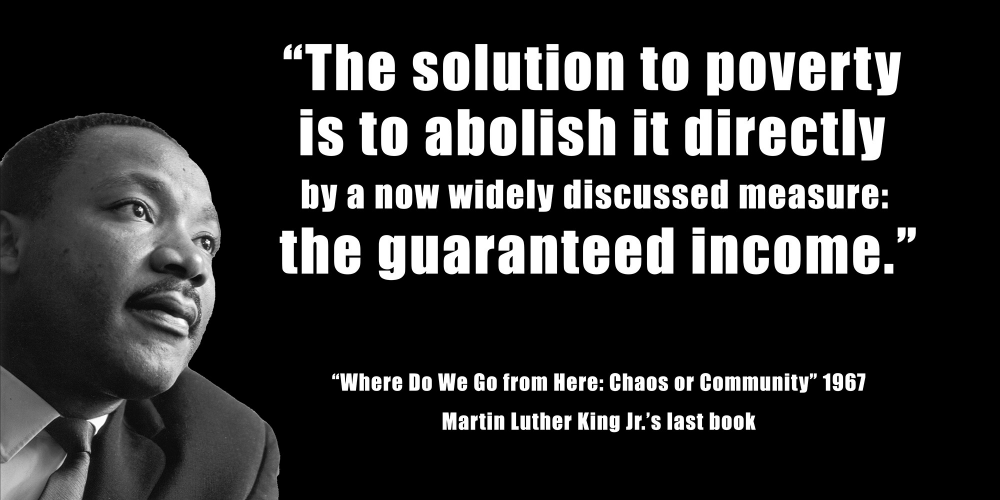

Notable Quotes

“I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective – the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed matter: the guaranteed income.”

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

…

“The evidence, as far as I can tell, is clear: as soon as you make people rich enough so that they are not living hand-to-mouth, then they start to become concerned with environmental degradation. So the biggest contributor to pollution — you could make a case, a strong case — that the biggest contributor to pollution isn’t wealth, but poverty. And if you raise people out of poverty, then they start to manage their environments properly because they can afford to look at the long run. So you would think that for the radical types that are hyper concerned according to their own self description with poverty and oppression, as well as environmental degradation, that they would look at the facts and say, ‘Oh my God, we can have a cake and eat it too!’ The faster we make people rich, the better off the planet is going to be.”

…

“Basic income is not a utopia, it’s a practical business plan for the next step of the human journey.”

— Jeremy Rifkin

…

“We need to make New York City the COVID comeback city, but also the anti-poverty city,” he said. “As mayor, we will launch the largest basic income program in the history of the country, right here in New York. We will lift hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers out of extreme poverty, putting cash relief directly into the hands of the families who desperately need help right now.”

…

“Essentially, in the future, physical work will be a choice. This is why I think long term there will need to be a universal basic income.”

……………

News Stories

• Elon Musk Says We Need Universal Basic Income Because ‘In The Future, Physical Work Will Be A Choice’ (Business Insider – 08/20/21)

• California Approves $35 Million Plan For Nation’s First State-Funded Guaranteed Income Program (Associated Press – 07/15/21)

• Basic Income Programs In Marin County And Oakland Exclude White People. Is That Legal? (Reason – 03/29/21)

• San Francisco To Give $1,000 A Month To Artists In Basic Income Program (Los Angels Times – 03/26/21)

• Andrew Yang Thinks New York City Should Adopt A Universal Basic Income (New York Post – 02/14/21)

• Why Mark Zuckerberg Wants To Give You Free Cash, No Questions Asked (Inc. – 06/19/17)

• Elon Musk Says Robots Will Push Us To A Universal Basic Income — Here’s How It Would Work (Make It – 11/21/16)

Important Resources

• Universal Basic Income (Wikipedia)

• Universal Basic Income Pilot Programs & Experiments (Wikepedia)

……………

……………

Stockton’s Basic-Income Experiment Pays Off

By Annie Lowrey

The Atlantic

A new study of the city’s program that sent cash to struggling individuals finds dramatic changes.

Two years ago, the city of Stockton, California, did something remarkable: It brought back welfare.

Using donated funds, the industrial city on the edge of the Bay Area tech economy launched a small demonstration program, sending payments of $500 a month to 125 randomly selected individuals living in neighborhoods with average incomes lower than the city median of $46,000 a year. The recipients were allowed to spend the money however they saw fit, and they were not obligated to complete any drug tests, interviews, means or asset tests, or work requirements. They just got the money, no strings attached.

These kinds of cash transfers are a common, highly effective method of poverty alleviation used all over the world, in low-income and high-income countries, in rural areas and cities, and particularly for households with children. But not in the United States. The U.S. spends less of its GDP on what are known as “family benefits” than any other country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, save Turkey. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program spends less than one-fifth of its budget on direct cash aid, and its funding has been stuck at the same dollar amount since 1996 — when the Clinton administration teamed up with congressional Republicans to turn it into a compulsory-work program. Those changes sliced into the safety net, allowing millions of people to fall through.

Most adults without children have no program to help them keep gas in the car and a roof over their head, no matter how poor they are. Most families with kids don’t have one either. In the United States, poverty is used as a cudgel to get people to work. We got rid of welfare for poor families’ and poor individuals’ own good, the argument goes. Give people money, and they stop working. They become dependent on welfare. They never sort out the problems in their life. The best route out of poverty is a hand up, not a handout.

Stockton has now proved this false. An exclusive new analysis of data from the demonstration project shows that a lack of resources is its own miserable trap. The best way to get people out of poverty is just to get them out of poverty; the best way to offer families more resources is just to offer them more resources.

The researchers Stacia Martin-West of the University of Tennessee and Amy Castro Baker of the University of Pennsylvania collected and analyzed data from individuals who received $500 a month and from individuals who did not. Some of their findings are obvious. The cash transfer reduced income volatility, for one: Households getting the cash saw their month-to-month earnings fluctuate 46 percent, versus the control group’s 68 percent. The families receiving the $500 a month tended to spend the money on essentials, including food, home goods, utilities, and gas. (Less than 1 percent went to cigarettes and alcohol.) The cash also doubled the households’ capacity to pay unexpected bills, and allowed recipient families to pay down their debts. Individuals getting the cash were also better able to help their families and friends, providing financial stability to the broader community.

“It let me pay off some credit cards that I had been living off of, because my household income wasn’t large enough,” one recipient named Laura Kidd-Plummer told me. “It helped me to be able to take care of my groceries without having to run to the food bank three times a month. That was very helpful.” During the study, Laura also experienced a spell of homelessness when the apartment building she was living in had a fire. The Stockton cash helped her secure a new apartment, ensuring that she could afford movers and a security deposit.

The researchers also found that the guaranteed income did not dissuade participants from working — adding to a large body of evidence showing that cash benefits do not dramatically shrink the labor force and in some cases help people work by giving them the stability they need to find and take a new job. In the Stockton study, the share of participants with a full-time job rose 12 percentage points, versus five percentage points in the control group. In an interview, Martin-West and Castro Baker suggested that the money created capacity for goal setting, risk taking, and personal investment.

“The big change was how it helped me see myself,” Tomas Vargas, another recipient, told me. “It was dead positive: I am an entrepreneur, I think of business ideas, I make business choices, I want to be financially stable.” When the program started, he worked in logistics. Now, in addition to nurturing his side projects, he is a case manager for individuals on parole.

He noted that receiving the money had made him more civically and politically engaged, if also more infuriated at the country’s scorn toward low-income households. “It’s like it’s a big game,” he said. “These people are living with a silver spoon, talking — but how about you walk this life? Have you ever even seen it?”

Finally, the cash recipients were healthier, happier, and less anxious than their counterparts in the control group. “Cash is a better way to cure some forms of depression and anxiety than Prozac or Ativan,” says Michael Tubbs, a former mayor of Stockton, who spearheaded the project. “So many of the illnesses we see in our community are a result of toxic stress and elevated cortisol levels and anxiety, directly attributed to income volatility and not having enough to cover your basic necessities. That’s true in the public-health crisis we’re in now.”

More work, less destitution, more family stability, less strained social networks, less stress, fewer incidences of homelessness, fewer skipped meals: This is what welfare could give the country.

And it just might. America’s welfare politics have shifted radically of late, in part because of the economic pressures felt by Millennials, the first generation in recent U.S. history likely to end up poorer than their parents. Two once-in-a-lifetime recessions, persistent wage stagnation, wild wealth and income inequality, the student-debt crisis, housing shortages, and a broader cost-of-living crisis have made redistributive policies much more palatable to them — and they’re now the country’s largest voting bloc. The pandemic has shifted U.S. welfare politics too, emphasizing the need for child-care benefits and demonstrating the power of cash as stimulus.

Right now, Democrats are pushing to send low- and middle-income parents $300 a month for each child younger than 6 and $250 a month for children ages 6 to 18 as part of President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus-relief package. The program would be temporary, but there is wide support for making it a permanent entitlement. Senator Mitt Romney, a Utah Republican, has put forward a proposal to eliminate TANF and replace it with a straightforward child allowance. A number of state, local, and nonprofit efforts are getting going too.

The Stockton demonstration project is ending. But a group Tubbs founded, called Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, is extending the initiative nationwide, with cities from Compton to Gary to Newark making plans to send low-income residents cash.

These policies are being described as child allowances, guaranteed incomes, and universal basic incomes — not as welfare — thus dropping some of the racist freight attached to TANF. But they are, in fact, a kind of welfare. Both as a policy and a concept, it is what so many Americans need.

………………

Busting The Myth Of ‘Welfare Makes People Lazy’

By Derek Thompson

The Atlantic

March 8, 2018

Cash assistance isn’t just a moral imperative that raises living standards. It’s also a critical investment in the health and future careers of low-income kids.

“Welfare makes people lazy.” The notion is buried so deep within mainstream political thought that it can often be stated without evidence. It was explicit during the Great Depression, when Franklin D. Roosevelt’s WPA (Works Progress Administration) was nicknamed “We Piddle Around” by his detractors. It was implicit in Bill Clinton’s pledge to “end welfare as we know it.” Even today, it is an intellectual pillar of conservative economic theory, which recommends slashing programs like Medicaid and cash assistance, partly out of a fear that self-reliance atrophies in the face of government assistance.

Many economists have for decades argued that this orthodoxy is simply wrong — that wisely designed anti-poverty programs, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, actually increase labor participation. And now, across the world, a fleet of studies are converging on the consensus that even radical welfare programs — including basic-income programs and what are called conditional cash transfers — don’t make people any less productive.

Most notably, a 2015 meta-study of cash programs in poor countries found “no systematic evidence that cash transfer programs discourage work” in seven different countries: Mexico, Nicaragua, Honduras, the Philippines, Indonesia, or Morocco. Other studies of cash-grant experiments in Uganda and Nigeria have found that such programs can increase working hours and earnings, particularly when the beneficiaries are required to attend classes that teach specific trades or general business skills.

Welfare isn’t just a moral imperative to raise the living standards of the poor. It’s also a critical investment in the health and future careers of low-income kids.

Take, for example, the striking finding from a new paper from researchers at Georgetown University and the University of Chicago. They analyzed a Mexican program called Prospera, the world’s first conditional cash-transfer system, which provides money to poor families on the condition that they send their children to school and stay up to date on vaccinations and doctors’ visits. In 2016, Prospera offered cash assistance to nearly 7 million Mexican households.

In the paper, researchers matched up data from Prospera with data about households’ incomes to analyze for the first time the program’s effect on children several decades after they started receiving benefits. The researchers found that the typical young person exposed to the program for seven years ultimately completed three more years of education and was 37 percent more likely to be employed. That’s not all: Young Prospera beneficiaries grew up to become adults who worked, on average, nine more hours each week than similarly poor children who weren’t enrolled in the program. They also earned higher hourly wages.

This finding has direct implications for the United States, where a core mission of the Republican Party is to reduce government aid to the poor, on the assumption that it makes them lazy. This attitude is supported by many conservative economists, who argue that government benefits implicitly reward poverty and thus encourage families to remain poor — the idea being that some adults might reject certain jobs or longer work hours because doing so would eliminate their eligibility for programs like Medicaid.

But this concern has little basis in reality. One of the latest studies on the subject found that Medicaid has “little if any” impact on employment or work hours. In research based in Canada and the U.S., the economist Ioana Marinescu at the University of Pennsylvania has found that even when basic-income programs do reduce working hours, adults don’t typically stay home to, say, play video games; instead, they often use the extra cash to go back to school or hold out for a more desirable job.

But the standard conservative critique of Medicaid and other welfare programs is wrong on another plane entirely. It fails to account for the conclusion of the Prospera research: Anti-poverty programs can work wonders for their youngest beneficiaries. It’s true north of the border, as well. American adults whose families had access to prenatal coverage under Medicaid have lower rates of obesity, higher rates of high-school graduation, and higher incomes as adults than those from similar households in states without Medicaid, according to a 2015 paper from the economists Sarah Miller and Laura R. Wherry. Another paper found that children covered by Medicaid expansions went on to earn higher wages and require less welfare assistance as adults.

“Welfare helps people work” may sound like a strange and counterintuitive claim to some. But it is perfectly obvious when the word people in that sentence refers to low-income children in poor households. Poverty and lack of access to health care is a physical, psychological, and vocational burden for children. Poverty is a slow-motion trauma, and impoverished children are more likely than their middle-class peers to suffer from chronic physiological stress and exhibit antisocial behavior. It’s axiomatic that relieving children of an ambient trauma improves their lives and, indeed, relieved of these burdens, children from poorer households are more likely to follow the path from high-school graduation to college and then full-time employment.

Republicans have a complicated relationship with the American Dream. Conservative politicians such as Paul Ryan extol the virtues of hard work and opportunity. But when they use these virtues to inveigh against welfare programs, they ignore the overwhelming evidence that government aid relieves low-income children of the psychological and physiological stresses that get in the way of embracing those very ideals. Welfare is so much more than a substitute for a paycheck. It is a remedy for the myriad burdens of childhood poverty, which give children the opportunity to become exactly the sort of healthy and striving adults celebrated by both political parties.

……………